The U.S. economy is in the middle of an awkward transition. Like a groggy bear roused from hibernation, the country is no longer dormant due to the pandemic but isn’t quite back in full form either. Millions remain unemployed, businesses are having trouble hiring, workers are still avoiding the office, and shortages of everything from lumber to computer chips have helped push up consumer prices. Economists are barking at one another about whether inflation could get out of control and Republican governors are booting their residents off of unemployment benefits to make them look for work. Some have wondered if the Biden administration spent too much money, too soon in its relief effort, setting us up for a hard landing down the line.

But if you look past the near-term wobbliness and pay close attention to the data that have been trickling in lately, there are ample reasons to be optimistic about where the economy is headed. It’s reasonable to think that by this year’s holidays, the long-predicted Biden boom will really be roaring, and the economic pain of the coronavirus crisis will finally be behind us. Here are seven reasons why.

Reason 1: Much of the Country Is Getting COVID Under Control

You can’t talk about the economy without talking about the pandemic, and there’s mixed news on that front.

Let’s get the bad out of the way first. Vaccination rates have seemingly started to plateau and are extremely uneven across the country, ranging from 85 percent for adults in Vermont to 46 percent in Mississippi. Experts warn that the more transmissible delta variant could cause severe regional outbreaks in parts of the country where relatively few adults have gotten their shots—which is to say, much of Republican America. The nation’s seven-day average case count has already started to edge up, and is rising in most states.

So what’s to celebrate? Even with the virus’s recent uptick, the country is still averaging close to its lowest number of daily cases since March 2020. Cases are down or flat in 21 states and the District of Columbia, while deaths and hospitalizations are both still trending down nationally. Three states—Massachusetts, Maryland, and Vermont—are now seeing fewer than one new infection per 100,000 residents each day, putting them on track to contain the virus and halt community spread, and several others are getting close to that threshold. And because vaccination rates are much higher among the elderly, who are generally most at risk from COVID, future outbreaks should be far less deadly than in the past (which is good, because it frankly seems unlikely any states are ever going back into a lockdown). America’s prognosis isn’t improving across the board. But in much of the country, especially heavily vaccinated blue states, the pandemic is finally coming under control even as normal life resumes.

Reason 2: The Worst of Inflation Might Already Be Behind Us

For months now, inflation has been the most talked about economic boogeyman in America. Consumer prices are rising fairly quickly at the moment, and there’s been a raging argument about whether they are poised to spiral out of control (as former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers has loudly warned) or are merely experiencing a temporary, post-pandemic bump as industries work through product shortages caused by snags in their supply chains (which is more or less Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell’s position).

But while the debate about it might burn on for a while, it’s possible that inflation is already starting to cool off, as Paul Krugman recently argued at the New York Times. Much of its recent spike was driven by surging prices in just a handful of industries such as used cars that appear to have peaked. The cost of crucial commodities such as lumber has come back to earth. And on a month-to-month basis, inflation rose more slowly in May than April.

Investors also seem to be relaxing a bit, as market measures of anticipated inflation have generally fallen since May. (One notable exception is the Cleveland Fed’s expectations tracker, though it still remains near all-time lows). That’s dealt a crucial blow to the argument hawks like Summers have, which hinges on the idea that business owners could start to expect higher inflation in the future and hike their own prices accordingly, setting off a vicious, self-fulfilling cycle. Instead, the markets haven’t lost sleep over the monster that’s supposedly waiting in their closet.

Reason 3: Consumer Spending Is Up—and Should Stay Up

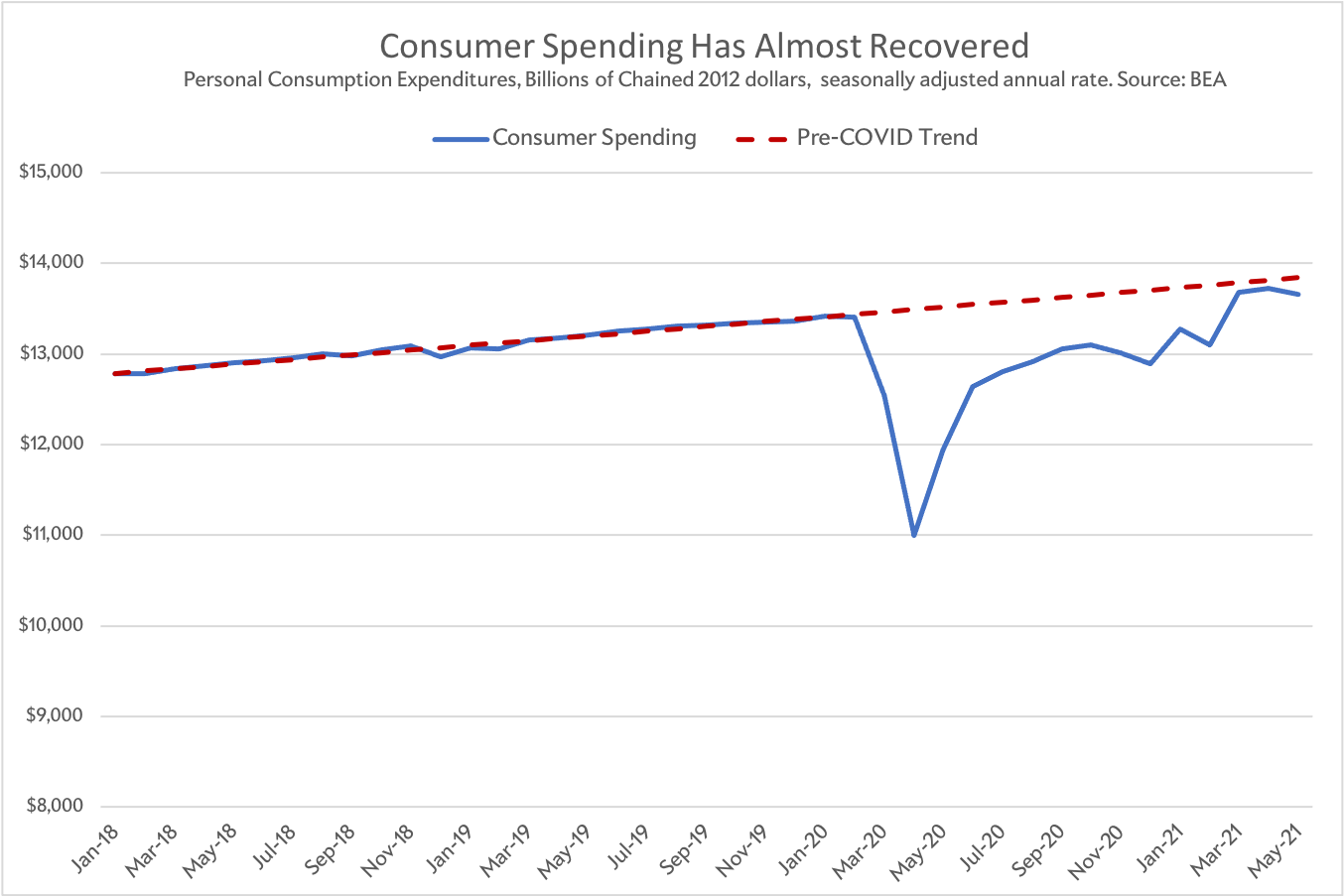

The United States is still down about 7.6 million jobs, but you’d never guess it from the amount of shopping people are doing these days. Despite a small dip from April, consumer spending was higher last month than in February 2020, and had nearly caught up to its pre-pandemic trend. Americans are snapping up cars, washing machines, and couches like mad.

The big question is whether we can keep it up. Many Americans have been relying on government aid to support themselves through the pandemic, and it’s unclear what will happen as families exhaust the money left over from their stimulus checks and federal unemployment programs expire. Will households be able to keep spending like they are now, or will they suddenly cut back? We don’t know for sure.

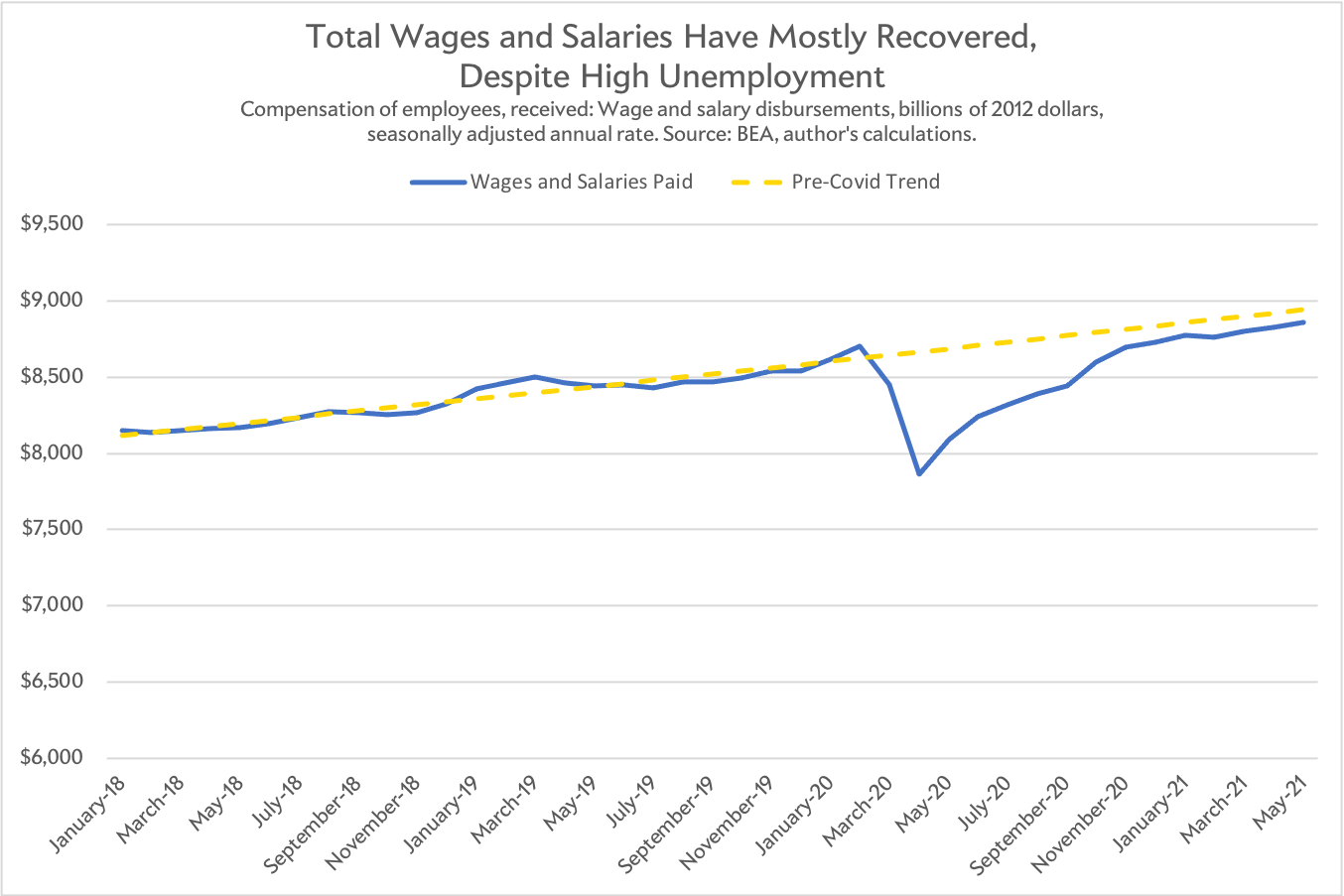

But there are good reasons to be upbeat about the answer. For starters, households saved record amounts of money while they were stuck at home in 2020, which suggests they still have pent-up spending power. Second, Americans have mostly recovered their collective earning power. Total wages and salaries quietly reached a new peak in May, and are trailing less than 1 percent behind their pre-plague trend. Pay has bounced back faster than employment, because the country’s missing jobs are largely concentrated in lower-wage service industries like hospitality.

We should still be concerned about what will happen to families who are relying on jobless benefits to get by when that aide disappears. But from a 10,000-foot perspective, the combination of savings and rising aggregate pay bodes well for consumer spending and the macroeconomy going forward.

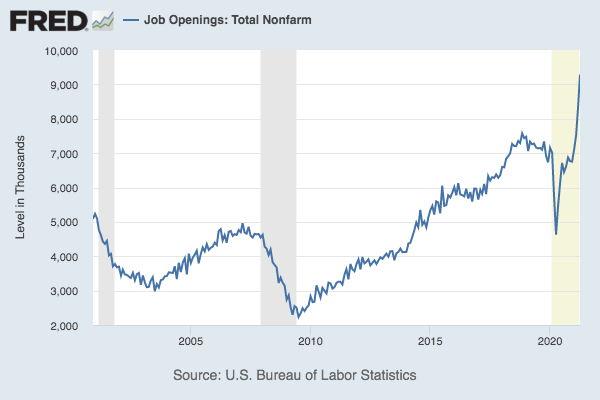

Reason 4: There Are a Ton of Job Openings

There are more positions available than ever in America, and business owners couldn’t be saltier about it. They’re allegedly desperate to hire but claim it’s impossible to find workers because people are choosing to stay home on unemployment benefits rather than answer a help-wanted ad.

Is there any truth to that? Maybe? Probably at least a little? I mean, nobody really knows. Again, Republican-led states have already started booting residents off benefits, but it’s not clear that’s making those people hunt for work any faster (the New York Times and Wall Street Journal news sections, which both do great econ coverage, just ran dueling articles making completely opposite arguments about the situation, which should give you a sense of what a Rorschach test it is).

But here’s the thing: When you set aside the cacophony of complaints from America’s fast-food franchisees and think about the long-term, you kind of have to bask in the surplus of job openings. That’s a great problem to have. First, the competition from employers is giving workers an edge and helping push up wages in some industries. Second, it means that when the boosted federal unemployment benefits officially expire in September, people will probably be able to find employment. It should be easier and safer for people to return to work by then too, since schools will be reopening, and more states with high vaccination rates will likely have contained the virus. Hiring is a little slow right now, but regardless of why, it very well could speed up by autumn.

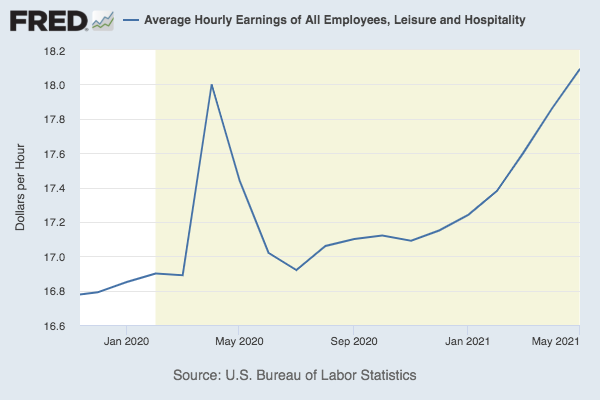

Reason 5: Real Wages Are Rising for Hospitality Workers

After a million stories about how small-business owners are ready to sacrifice their first born if that’s what it takes to fill a job opening, you might think wages would be surging across the board. That’s kind of the case—hourly pay among all workers did rise quickly in April and May. The problem is that those gains are currently being outstripped by inflation.

But it’s a different story in the leisure and hospitality business. There, wage growth has shot up by about 5 percent since January, well above the pace of the consumer price index. America’s waiters, cooks, bartenders, and hotel maids are getting a much-needed pay bump.

Reason 6: Restaurants and Bars Are Recovering

The coronavirus recession was, for the most part, a services-sector recession—restaurants, hotels, airlines, gyms, movie theaters … basically any space where people spend time in rooms full of lots of other people had to shut down and lay off workers. Meanwhile, sales of durable goods exploded as half of America decided to build a new deck or equip a home gym.

That dynamic hasn’t entirely faded yet. As of May, households were still spending more than normal on goods (up 19 percent since the pandemic started) than on services (down about 1 percent since the plague began).

And while some parts of the services sector are recovering, others are still stuck in the pits. Spending at restaurants has rebounded. But spending at hotels, sports, live entertainment, and movie theaters is all still down massively.

Here’s the glass-half-full way to interpret that graph: First, the dining industry is economically important on its own. But also, if you think about the crowds at restaurants and bars as a leading indicator of people’s willingness to go out and be merry in a crowd, then the number of people packing dining rooms and bars right now is a pretty positive omen for services more broadly. If Americans will jam into a crowded dive to get a Miller Light right now (and they clearly are), then they’ll eventually flock to concerts too as time goes on and states continue lifting capacity restrictions.

Reason 7: Business Productivity Is Booming

You might be wondering how it is that restaurant sales have recovered even though they’re employing so many fewer workers than in the Before Times. The answer likely lies partly in the QR codes you’ve been scanning every time you want to pull up a menu, instead of waiting for a server. The pandemic forced businesses to make do with fewer employees, leading many to invest heavily in new software to automate parts of their business. The result, as the Wall Street Journal’s Greg Ip recently observed, is that we seem to be “in a productivity boom.” By the end of the first quarter of 2021, output per hour was up 4.1 percent compared with a year earlier, the biggest increase in a decade.

Part of the reason productivity jumped so much during 2020 was simply that businesses laid off so many workers in the service sector, where productivity tends to be lower. The startling thing, as Bloomberg Opinion’s Noah Smith has explained, is that productivity growth actually sped up at the beginning of 2021, just as many of those employees returned to work—the opposite of what you’d expect to happen. Investment in software also accelerated from January to March. That suggests a more fundamental shift is taking place: The crisis may have finally made some businesses move into the 21st century.

Productivity growth is a crucial ingredient to a healthy, expanding economy. It’s how we learn to do more with less labor, freeing people to do other, more valuable jobs. It also allows businesses to raise wages without having to raise prices, since their employees generate more revenue. But despite the last decade’s worth of advances in tech, productivity was extremely sluggish in the years after the Great Recession. That’s what makes this recent burst so exciting; it’s not just the silver lining of a terrible year, but even, potentially, the end to a long period of relative stagnation. But will our productivity growth spurt continue? Some economists, like MIT techno-optimists Erik Brynjolfsson and Georgios Petropoulos, think it might. And if they’re right, we could be in for the sort of economic run the U.S. hasn’t seen in a long, long time.