You might think that the $17,000 bills that Texas electricity providers are sending to customers who kept their lights on during last week’s historic storm reflect red state libertarian ideology run amuck. But you would be wrong.

They are actually the product of the exact same approach to markets reflected in the congestion-pricing plan for midtown Manhattan adopted by the New York State legislature in 2019, in the way Broadway priced tickets for shows like The Lion King and Wicked before the pandemic, and the way airlines have been pricing seats for years.

The problem is not ideological but intellectual, and has its roots in something a Democratic appointee to the New York Public Service Commission did to the pricing of electricity in New York State back in 1975. That thing is called marginal-cost pricing, and it became part of American life thanks largely to the efforts of one man: economist Alfred Kahn.

The idea behind marginal-cost pricing is simple enough. If you have a resource like electricity that is in short supply because, say, all your natural gas pipelines and wind turbines have frozen over, then you need to ration the resource. One way to do that is to leave prices alone and just let the resource run out, effectively rationing access to those who use it first. But another—the marginal-cost approach—is to raise prices and ration the resource to those who are willing to pay the most for it. That’s what electricity companies like Griddy did in Texas, and why we saw such mind-boggling bills.

Kahn liked that kind of approach because it seemed to encourage conservation while preserving freedom of choice: The high prices encourage those who place a low value on the resource to use less of it, while maintaining—at least in theory—the option for those who really need it to get access in a pinch by opening their pocketbooks.

As Thomas K. McCraw relates in a mini-biography of the great deregulator, Kahn took control of New York’s utilities at a time—1974—when the hallmark of American business had, for three post-war decades, been abundance, not shortage, and pricing structures reflected that.

Electricity pricing in particular was dominated by the “declining-block rate structure,” which today reads like a fever dream: It was designed to encourage consumption of plentiful electricity by reducing the price per kilowatt the more electricity you used.

The oil shocks and stagflation of the 1970s, not to mention growing awareness of the environmental costs of electricity, put an end to the postwar plenty. People would need to conserve, and Kahn’s answer was that those who cannot afford to pay higher prices should be the ones to do it.

Put that way, it is hard to understand how such an obviously inequitable approach to rationing ever got off the ground. But those were the Watergate years, and the approach had something powerful going for it, which also explains its continued bipartisan appeal: It takes the rationing process out of the hands of government.

When you ration with price, no one decides who gets to keep the lights on and who doesn’t. The impersonal market decides.

So it was none other than President Jimmy Carter, riding a wave of deregulatory fervor stoked by Democratic Sen. Edward M. Kennedy and his star staffer, future Supreme Court Associate Justice Stephen Breyer, who brought Kahn to Washington in 1977 and put him in charge of deregulating the airlines.

Kahn succeeded, and one of the first things the airlines did with their new freedom was to build marginal-cost pricing into their nascent computer reservations systems, giving rise to the enormous fares charged for seats on full planes that fliers today know and detest so well.

From there, the marginal-cost pricing ethos spread, and today it has become the default rationing mechanism for businesses and governments alike, from Uber surge-pricing your rides to states surge-pricing your highway tolls.

The only problem, as the Public Utility Commission of Texas found out last week, is that it doesn’t actually work—at least not in situations of extreme shortage when rationing is most needed—and that’s before considering the inequity associated with allocating access based on ability to pay.

As the storm hit on Feb. 13, Griddy, a firm that sold many of the contracts that led to astronomical prices, urged customers to find other providers. The company knew its prices would spike because it had taken advantage of Texas’s almost completely deregulated electricity market to implement the ultimate in marginal-cost pricing for residential customers: wholesale rates that would soon be driven by market forces to levels at which those who could afford to pay the most would have all the electricity they wanted, and everyone else none.

But only if freezing customers made heating decisions with their finances in mind. Some did, and bailed out of Griddy’s contracts or kept the heat off, but many kept the heat on, even if they knew they couldn’t afford it. So much for the magical power of price to ration without government intervention.

The disconnect between the reality and Kahn’s theory, which is second nature now to regulators, is almost too painful to read. Two days after Griddy anticipated the tsunami of overcharges, the Public Utility Commission of Texas chastised the nonprofit that manages Texas’s electricity markets for not doing more to raise prices for all Texans, not just those contracting with Griddy. If “scarcity is at its maximum,” wrote the Commission on Feb. 15, the market price for electricity “should also be at its highest.”

Texas was already experiencing blackouts and, unfortunately in the Commission’s eyes, they were striking randomly rather than affecting only those too poor to pay. In fact, Griddy’s higher prices were not keeping demand down anyway, only cleaning out Texans’ life savings.

But the problem with marginalism goes deeper than just the fact that people don’t always respond to price signals. Even when they do respond, there’s no reason to suppose that those who choose to conserve really place a lower value on the resource than those who choose to spend. It is a point almost too obvious to repeat: We all know that being able to afford something, and really wanting or needing it, are two very different things. How that basic fact could have been forgotten over 50 years of regulatory policy is hard to understand.

Fortunately, we are starting to return to our senses. Just as dazed Texans were getting their electricity bills last week, lawyers and economists from around the world were meeting at Inframarginalism & Internet, a conference devoted to developing an alternative to Kahn’s approach.

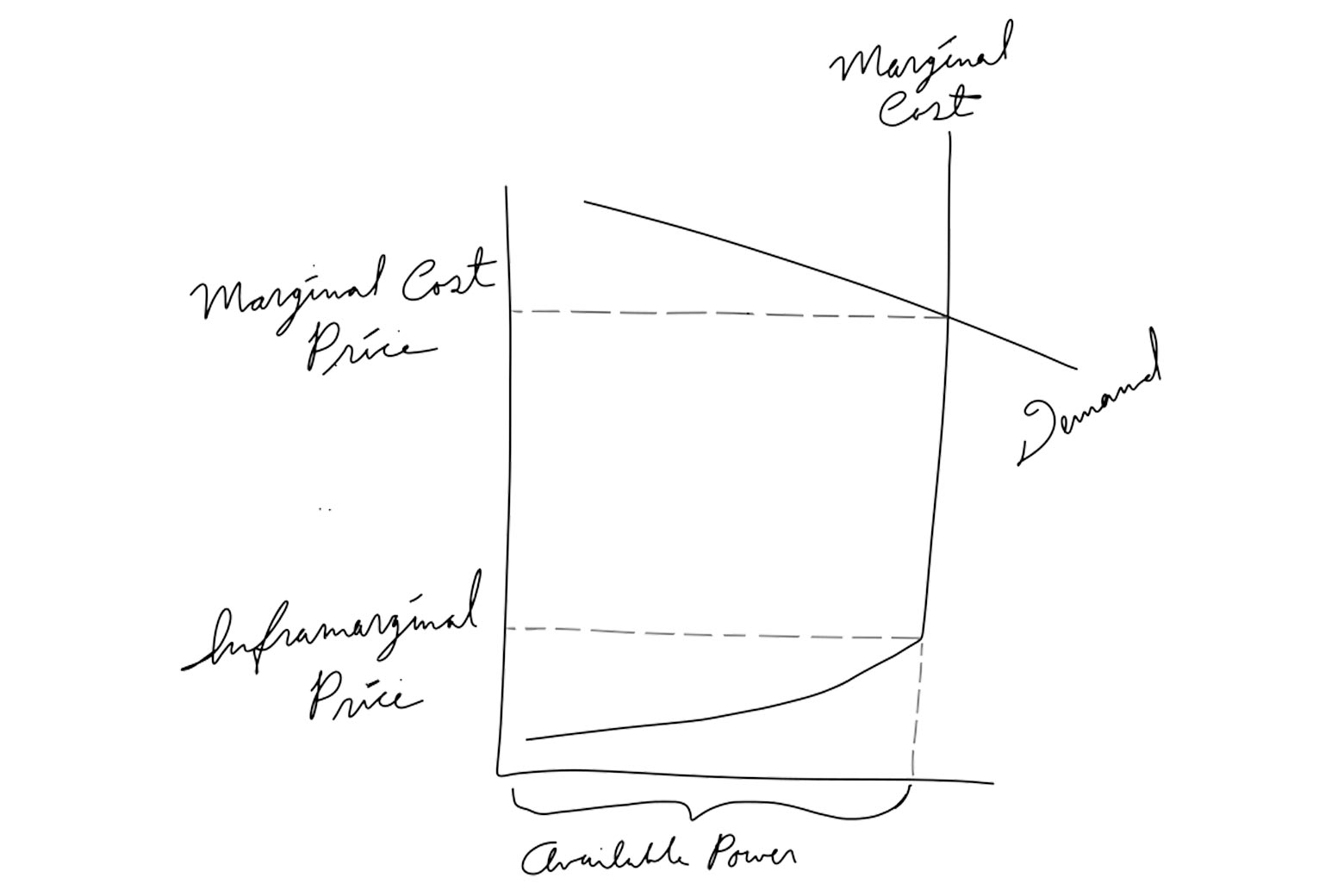

Kahn’s marginalism (and that of the Chicago School that informed his thinking) holds that price should be set equal to the cost of producing the next unit of output. When there is a shortage, that cost is infinite, which is why prices can go sky-high, as the graph I sketched out below shows. Inframarginalism holds that price should be set equal to the cost of all the other units—the inframarginal units—to keep profits low and consumer welfare high.

That means that access to a scarce resource must be rationed based on something other than ability to pay. Need is a good alternative, and big data and the internet make it easier than ever for regulators to identify the needy and route resources to them. It’s not hard to imagine a smart Texas power grid that would have used data to ration power to the coldest hours of the night, the snowiest regions of the state, or even the towns with the least firewood to burn.

When need can’t easily be determined, the principle of first-come-first-served, which many supermarkets implemented for online ordering during pandemic lockdowns, works just fine. So long as price covers production cost (including a reasonable return on investment) there is no effect on output, but markets become a whole lot more equitable.

Defenders of marginal-cost pricing sometimes argue that high prices send a signal to sellers that there is money to be made by ramping up output to end the shortage. But they can’t mean a true shortage—like the one Texas faced—because by definition output can’t be ramped up in the short term. And anyway, selling out sends the same signal: If rolling blackouts didn’t clue Texas power companies into the possibility of selling more power if they could find it, probably nothing could.

So does Kahn’s work on the New York Public Service Commission mean that what happened in red state Texas could also happen in blue state New York, or elsewhere for that matter? Fortunately, the general answer is no.

Although Kahn did succeed at getting New York to embrace marginal-cost pricing in principle, and most other states have followed suit, few have taken it to the extreme Kahn had in mind. In states such as New York, commercial and industrial customers do pay higher prices when electricity supply runs short (and residential customers can opt in to plans that have that effect), but the magnitude of price increases is fixed in advance, so in the case of an extreme shortage, the power will go out before prices can go through the roof.

Which is the way it should be.