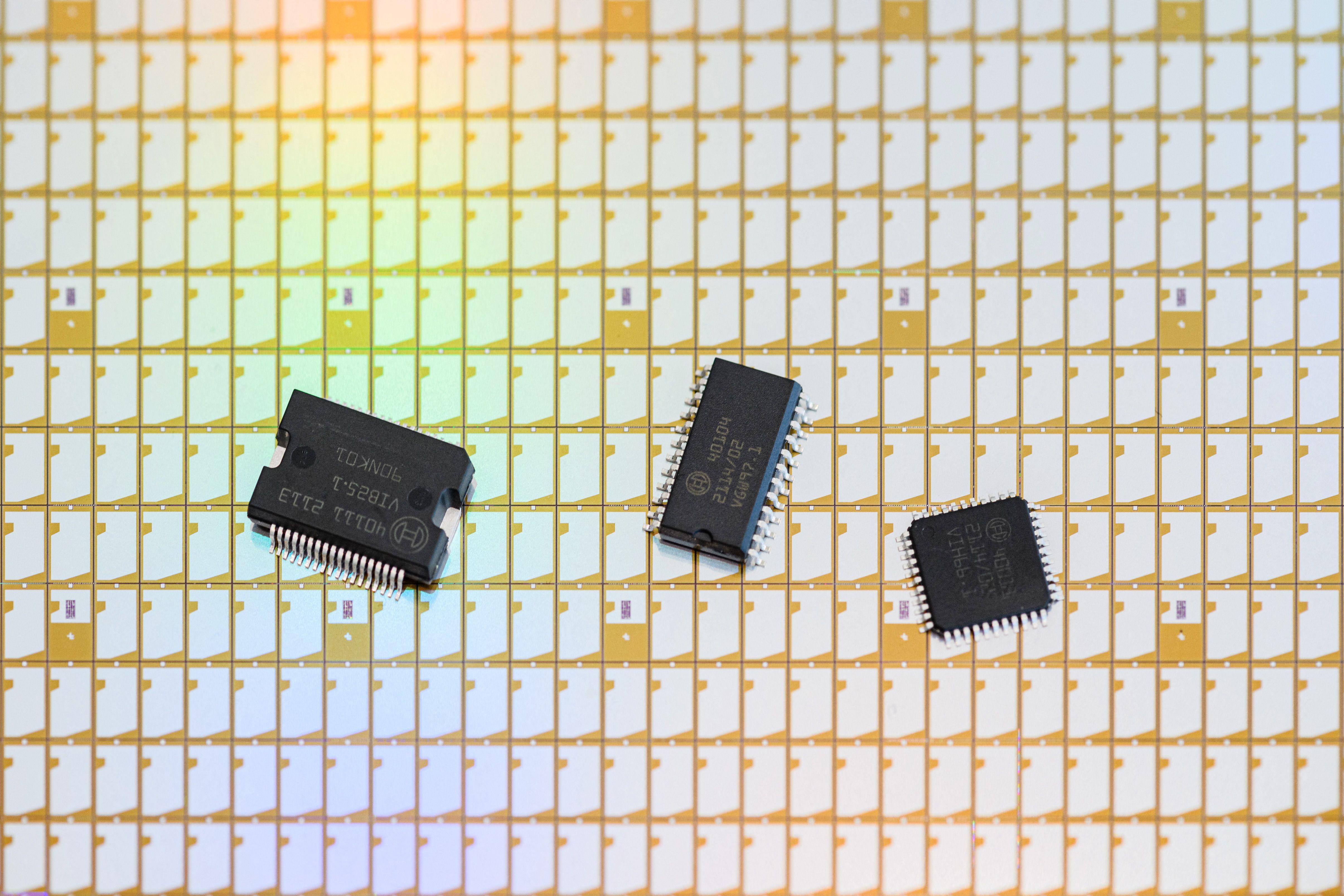

The shortage of semiconductors, the chips that help everything from cars to laptops to toasters to function, has been a persistent snarl in the supply chains for electronics throughout the pandemic. This issue, like other product frustrations over the last year or so, was supposed to work itself out—either as manufacturing ramped up to meet demand, or as demand cooled down. But look around and you’ll still see that it’s still tough to find items like gaming consoles and smartphones. Instead of fading, the chip problem has become so unmanageable that it’s on track to outlast the lockdowns and closures that triggered the shortage in the first place.

As with any complex supply-chain quagmire, there are a number of different factors that are building on one another, which means there isn’t one simple fix to the semiconductor shortage. Here’s a breakdown of what’s likely to making it so bad—and a clue to when you’ll finally be able to get your hands on a Nintendo Switch.

Demand

At the beginning of the pandemic, sales of desktops, laptops, smartphones, and other essential work-from-home devices shot through the roof as offices became uninhabitable. Sales of game consoles and crypto-mining rigs also exploded as people were looking to fill their free time. The sudden shortage of chips that power these products led to a wave of panic-buying—as was the case with toilet paper and dried goods and any number of other things early in the lockdown—that is swamping manufacturers to this day. Production of semiconductors for other goods, particularly cars, initially went down as people didn’t need them early on in the pandemic, but demand recovered more sharply than expected and manufacturers suddenly had to start ordering large amounts of chips again. Yet even after the vaccine rollout and partial reopening of society, demand for products that require lots of chips continues to rise, and there’s little indication that this appetite for electronics will abate anytime soon. It’s likely that the pandemic has permanently changed certain modes of working and communicating to rely more heavily on electronic (that is, semiconductor-driven) devices. “We’ve gotten so comfortable with this internet communication. Going forward, there’s going to be impacts on how many of us work, and as a result I think the demand for electronics is going to remain high,” said Chris Ober, a materials engineering professor at Cornell University.

Building New Factories

A number of chip companies have broken ground on new facilities to increase their manufacturing capacities. The completion of these projects will be key in ending the shortage, yet it’s unclear when exactly they will start to bear fruit. Indeed, many executives of semiconductor companies have been basing their varying predictions about the continuing shortage on these expansions. One of the more optimistic prognosticators, Advanced Micro Devices CEO Lisa Su, said at a conference in September that new manufacturing plants are likely to considerably alleviate supply-chain bottlenecks by the second half of 2022. (This is what counts as hopeful.) Matt Murphy, CEO of the semiconductor developer Marvell Technology, isn’t quite as rosy, telling CNBC in early October that factory capacity expansions won’t help to boost production until 2023 or 2024. GlobalFoundries, a major chipmaker based in New York, also recently reported that its production capacity will be maxed out through the end of 2023.

The process of erecting a semiconductor factory is extremely capital-intensive, time-consuming, and complex. Ars Technica reports that building costs range from $5 billion to $10 billion; this astounding price tag makes some companies hesitant to undertake such a project, which can take years, since the investment will only be worth it if demand continues to rise into the far future. There’s also the possibility that various companies building their factories all at once will increase global manufacturing capacity beyond demand. “The worry is that if the timing is not correct, they can never get their money back. There’s a high profit margin now, but once more players enter, the profit margin cannot be maintained,” said Edwin Kan, an electrical and computer engineering professor at Cornell University. “Even though it’s presented as a global crisis, companies worry that all these people entering the market will make supply overrun demand.”

Labor

Beyond having enough plants to meet demand, the semiconductor industry is also having issues finding workers to staff them. IPC, a trade group representing semiconductor companies, reported in late September that nearly four in five manufacturers are struggling to find qualified workers, and that the problem is particularly acute in Europe and North America. Workers need specialized training to handle the toxic chemicals used in the semiconductor manufacturing process, which creates another bottleneck in increasing staffing levels. Companies are now offering higher wages, more flexible hours, and training and educational opportunities in an attempt to entice new recruits. The Oregonian recently reported that Intel, the largest semiconductor company in the world, is even running a “help wanted” ad campaign on TV and radio programs aimed at students who are still in college to work part time when they’re not in class.

Equipment and Materials

It turns out that many of the physical objects needed to actually make semiconductor chips have been in short supply as well. The substrates that make up printed circuit boards, the surface on which chips are mounted, have been hard to come by. These circuit boards are essential to allow chips to communicate with one another. Ron Olson, director of operations for Cornell’s NanoScale Science and Technology Facility, further notes that certain miscellaneous items tangential to the manufacturing process are now on back order, such as personal protective equipment and gas lines.

Building new factories and expanding capacity in existing ones puts stress on supply chains for the equipment that manufactures the semiconductors. “We tend to focus on the chip foundries, but the chip foundries need a whole bunch of stuff in order to become a chip foundry, and that stuff is held up as well,” said Ober. “If everyone is trying to build them, then they’re all trying to buy the same equipment.” There are a limited number of companies that make this highly specialized equipment, so there are lengthy lead times. In addition, installation of the equipment in a plant and testing the reliability is its own time-consuming process. “Buying equipment takes half a year to a year, and then after that you’ve got to do all the process development and qualify the equipment,” said Olson. “All these things take time.” Clearly.