The Prices on Your Monopoly Board Hold a Dark Secret

The property values of the popular game reflect a legacy of racism and inequality.

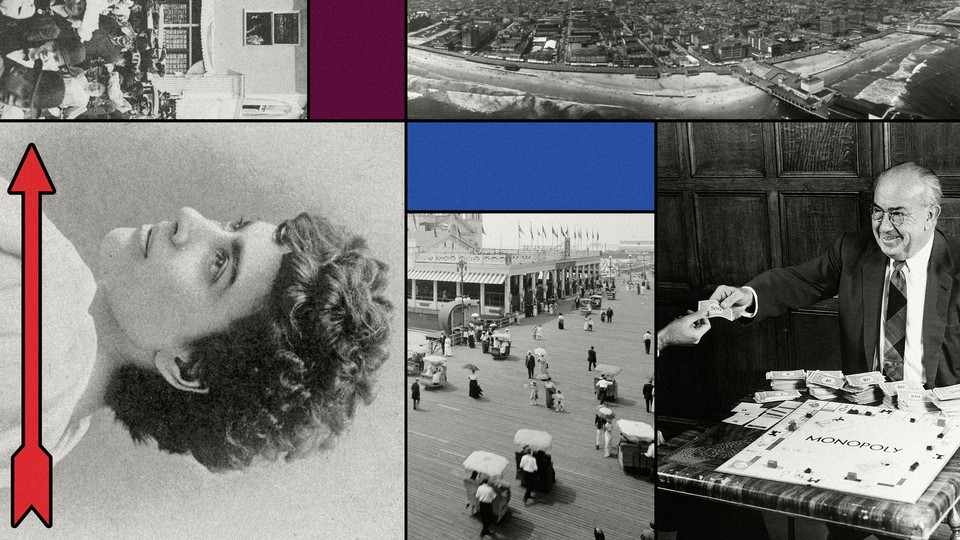

Take a good look at a Monopoly board. The most expensive properties, Park Place and Boardwalk, are marked in dark blue. Maybe you’ve drawn a card inviting you to “take a walk on the Boardwalk.” But that invitation wasn’t open to everyone when the game first took on its current form. Even though Black citizens comprised roughly a quarter of Atlantic City’s overall population at the time, the famed Boardwalk and its adjacent beaches were segregated.

Jesse Raiford, a realtor in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in the early 1930s and a fan of what players then called “the monopoly game,” affixed prices to the properties on his board to reflect the actual real-estate hierarchy at the time. And in Atlantic City, as in so much of the rest of the United States, that hierarchy reflects a bitter legacy of racism and residential segregation.

Cyril and Ruth Harvey, friends of Raiford’s who played a key role in popularizing the game, lived on Pennsylvania Avenue (a pricey $320 green property on the board); their friends, the Joneses, lived on Park Place. The Harveys had previously lived on Ventnor Avenue, one of the yellow properties that represented some of Atlantic City’s wealthier neighborhoods, with their high walls and fences and racial covenants that excluded Black citizens.

The Harveys employed a Black maid named Clara Watson. She lived on Baltic Avenue in a low-income, Black neighborhood, not far from Mediterranean Avenue. On the Monopoly board, those are priced cheapest, at $60.

Atlantic City served as a hub to some of the 6 million Black Americans who left the Jim Crow South seeking new opportunities in the North as part of the Great Migration. It was the “first mass antiracist movement of the twentieth century,” Ibram X. Kendi writes in Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America. But, he added, “when migrants reached northern cities, they faced the same discrimination they thought they had left behind, and they heard the same racist ideas.”

For white Americans, “Atlantic City, like all mass resorts, manufactured and sold an easily consumed and widely shared fantasy,” Bryant Simon, a history professor at Temple University and the author of Boardwalk of Dreams: Atlantic City and the Fate of Urban America, told me. “Southernness is used to sell that fantasy in the North,” he explained, pointing to marketing that focused on the stereotypically white, southern luxury of hiring Black laborers to shuttle visitors around in rolling chairs, wait on their tables, or otherwise serve them. Jim Crow, Simon said, existed everywhere. Around the time that Monopoly was taking hold in Atlantic City, ballots there were marked “W” for white voters and “C” for “colored” voters, Simon said. It would take countless demonstrations and protests and a long struggle by the city’s Black residents to secure their civil rights, but the Monopoly board records a world of ubiquitous racism.

Although Black residents and tourists could work at hotels such as the Claridge, between Park Place and Indiana Avenue, they were not permitted to dine or lodge there. Some hotels even offered white guests the option of having only white workers wait on them. Black employment was largely limited to the tourist industry, as political and municipal jobs were reserved for white residents.

Atlantic City’s Boardwalk staged minstrel shows, but Black people were largely barred from attending any form of entertainment on the famed Steel Pier. Schools in the area were segregated, clerks at many hotels did not check in Black tourists, and what antidiscrimination laws were on the books were not enforced, Simon said. If Black residents were found to be on a beach that wasn’t designated for Black patrons only, “it wasn’t just like they were run off,” Simon said. “They would be arrested. The police enforced segregation in the city.”

When the Washington, D.C., resident Elizabeth Magie received a patent in 1904 for the game that we would come to know as Monopoly, she had designed it as a teaching tool. She aimed to illustrate the evils of economic inequalities and the consequences of capitalism unhinged.

As Magie’s game proliferated in the early 20th century, many people localized the boards to reflect their own communities: A New York City version featured Broadway, Chicago players added the Loop and Lake Shore Drive, and Bostonians moved their tokens through the Common. Cartography and cardboard merged as folk game makers imposed their own realities onto their dining-room tables.

By the late 1920s and early 1930s, versions of Magie’s game had made their way to Atlantic City, where Quakers such as the Harveys played it, chronicling what they saw in their own community. Those game makers worked with oilcloth and paint at home, using scrap paper or Old Maid cards for Community Chest or Chance cards, according to court records that surfaced decades later. It was a version of the Atlantic City Monopoly board that would eventually be mass-produced by Parker Brothers starting in the mid-1930s, and that is still sold today.

The board didn’t just record exclusion and discrimination; it also hinted at the dynamic life of the diverse city where the game was played. The city’s thriving Black business community centered on Kentucky Avenue, often known as “Ky. at the curb.” The area featured movie theaters and the famed Club Harlem. The Count Basie Orchestra played at the Paradise Club on Illinois Avenue, and Indiana Avenue had a Black beach—until white owners of a nearby hotel complained.

Farther down the board, restaurants run by Chinese Americans thrived on Oriental Avenue and Jewish delis could be found in the area. Other immigrants, notably those from Italy or Ireland, had similar enclaves not far away, echoing the lines that were drawn in nearby cities such as New York and Philadelphia. New York Avenue hosted some of the first gay bars in the country.

In the decades after the Atlantic City version of the Monopoly game became an international blockbuster during the Great Depression, the city suffered. New vacation destinations, including Disneyland, copied the approaches pioneered by Atlantic City, and as car and air travel expanded, the rail connections that had once made Atlantic City so convenient began to seem comparatively slow. White residents abandoned the city in droves; many of the inequalities inscribed in the city’s geography kept Black residents from following. Decades of poor political and business decisions by civic leaders compounded the city’s struggles.

The impact of the decisions made during Monopoly’s heyday is still felt today. Atlantic City is a “redlined epicenter” of the state, according to the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice, and it leads the state in foreclosures. The rate of white homeownership in New Jersey stands at 77 percent, but Black homeownership is scarcely half of that, at 41 percent. A typical Black family in New Jersey has less than two cents for every dollar of wealth held by a typical white family.

In her book Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, the journalist and historian Isabel Wilkerson writes, “Caste is insidious and therefore powerful because it is not hatred, it is not necessarily personal. It is the worn grooves of comforting routines and unthinking expectations, patterns of a social order that have been in place for so long that it looks like the natural order of things.”

Seldom do we treat board games as important cultural artifacts akin to paintings, songs, or movies. But commonplace objects tucked into our closets and handed down from one generation to another can tell us important things about our past. Sometimes, they reflect patterns that many Americans, particularly those who have benefited from them, don’t even think to question, arrangements that have been naturalized over time.

Magie, an outspoken feminist, throughout her life aligned herself with groups that were also passionate about the pursuit of justice. Over time, most of her original aims in creating the game were forgotten, and her own role was largely erased. In the end, she received only $500, and no residuals, for the game she had invented.

But if Magie’s goal was to highlight the injustices of American society, Monopoly still offers us the chance to understand how deep-seated those injustices can be. We simply have to look closely enough at the board.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.