By now, you’ve noticed. Your corner CVS is full of eerily empty shelves and low on detergent. West Elm says it will be months before you can get that one coffee table. There’s a wait list for the Nikes your hypebeast boyfriend has been coveting. Thanks to the disruptions in global supply chains that have sprung from the coronavirus crisis, Americans are confronting a widespread shortage of consumer goods that’s become just about impossible to miss.

Supply chain problems have dogged the world economy all through the pandemic. Early on, panic hoarding and problems in particular industries, such as semiconductors, made it impossible for shoppers to get their hands on specific items like Clorox wipes or a new Playstation 5. But those narrower problems have sprawled into a much broader mess. For much of 2021, retailers have been running out of just about everything from diapers to dress shoes. The entire great machine of international logistics, which moves goods from factories in Shenzhen to Walmarts in St. Louis, is jammed up.*

Lately, this situation has become a growing source of political anxiety for the White House thanks to the looming holiday shopping season, and the prospect of backlash from angry parents who have trouble finding gifts. On Wednesday, President Joe Biden laid out the beginning of his administration’s plan to save Christmas, announcing that it had reached a deal to keep the Port of Los Angeles operating 24 hours a day, seven days a week, in order to clear its massive backlog of cargo. Together with the Port of Long Beach next door, the docks in L.A. help process 40 percent of the shipping containers that arrive in the United States. But record numbers of boats have been stranded outside the port in recent months as the flow of goods has overwhelmed its unloading capacity.

How much Biden can actually do to straighten things out is unclear. But while the situation is a pain for consumers and a genuine threat for businesses that stand to lose sales if they can’t stock their shelves, it’s also important to understand that the Great Supply Chain Snarl of 2021 isn’t just a logistical Rubik’s Cube waiting for some inventive solution. Instead it’s better understood, to a large extent, as the downside of the success we’ve had supporting the economy through the pandemic. The core problem is simple: Americans are currently buying a record amount of stuff, and that spending binge is crashing the transport and warehousing network meant to move it all.

“We’ve spent decades optimizing supply chains to carry a very specific amount of cargo during very specific times of the year across very specific modes of transportation,” says Nathan Strang, an expert on ocean trade logistics at the supply chain tech and consulting firm Flexport. “As soon as we exceeded the design capacity of those systems, it broke.”

When you look closely at all of the small fractures that have contributed to the world’s supply chain crackup, it really can begin to look maddeningly complex. As the Atlantic’s Derek Thompson put it, global commerce is currently being choked by “a veritable hydra of bottlenecks.” China’s “zero tolerance” policy for the coronavirus led it to shut down a major shipping terminal after a single infection and has slowed traffic at other ports. Lately, rolling power outages in the country have closed factories. Vietnam’s clothing and shoe plants, which companies like Nike rely on, were paralyzed by COVID lockdowns earlier this year. The world has also been bedeviled by shipping container shortages, made worse by bizarre pricing incentives that have led companies to send the boxes back from the U.S. to Asia empty, leaving American agricultural exporters in the lurch. Meanwhile, the world’s semiconductor shortage has lingered on, stalling car and electronics production; earlier this week, it was reported than Apple is expected to cut iPhone production by 10 million because it simply can’t get enough chips.

Even when goods do make it to American shores, they’ve ended up stalled at ports thanks to a “complicated and insidious series of overlapping problems” as the New York Times explains. These individual breakdowns all compound, with one delay cascading into another, and together, they all help explain why you can’t find any Tide at Walgreens, or the Honda CR-V in the color you want.

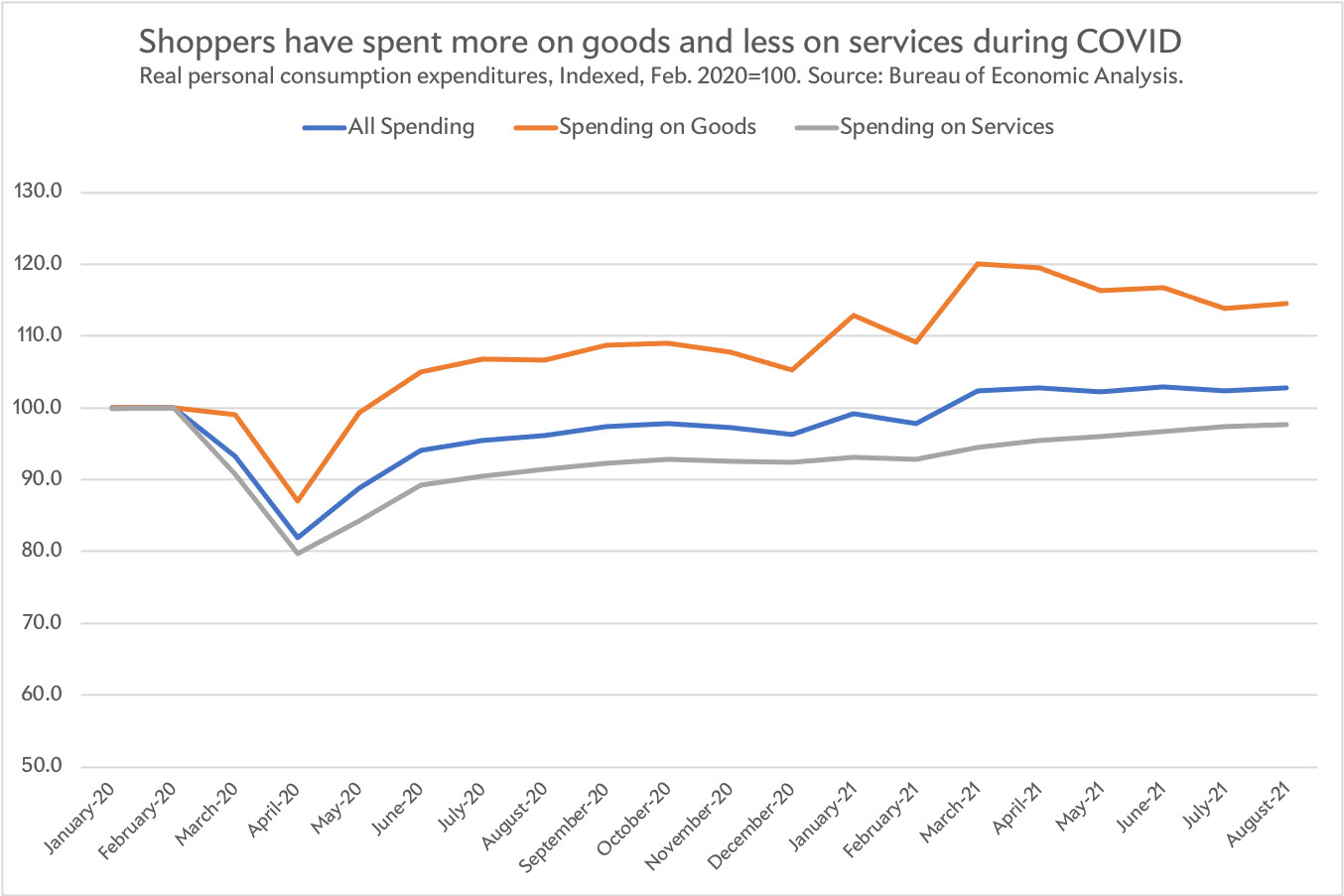

But if you look at the bigger picture, it becomes clear the problems in the U.S. largely flow from one key factor: We are simply buying an enormous amount of things. When the pandemic began, and Americans found themselves unable to go out, households suddenly shifted their spending to goods from services. With the money they saved skipping restaurant meals, movie trips, and vacations, people spruced up their living rooms with new couches, built out home offices, and bought themselves some exercise equipment. Stimulus checks helped fuel the shopping as many employees who’d kept their jobs splurged on TVs and cars. Economists widely expected that, as the pandemic faded, Americans would revert back to their older spending patterns. But that hasn’t happened yet, thanks in part to the delta wave. By August, inflation-adjusted spending on goods was up 14.5 percent compared with pre-pandemic, while services were still down more than 2 percent.

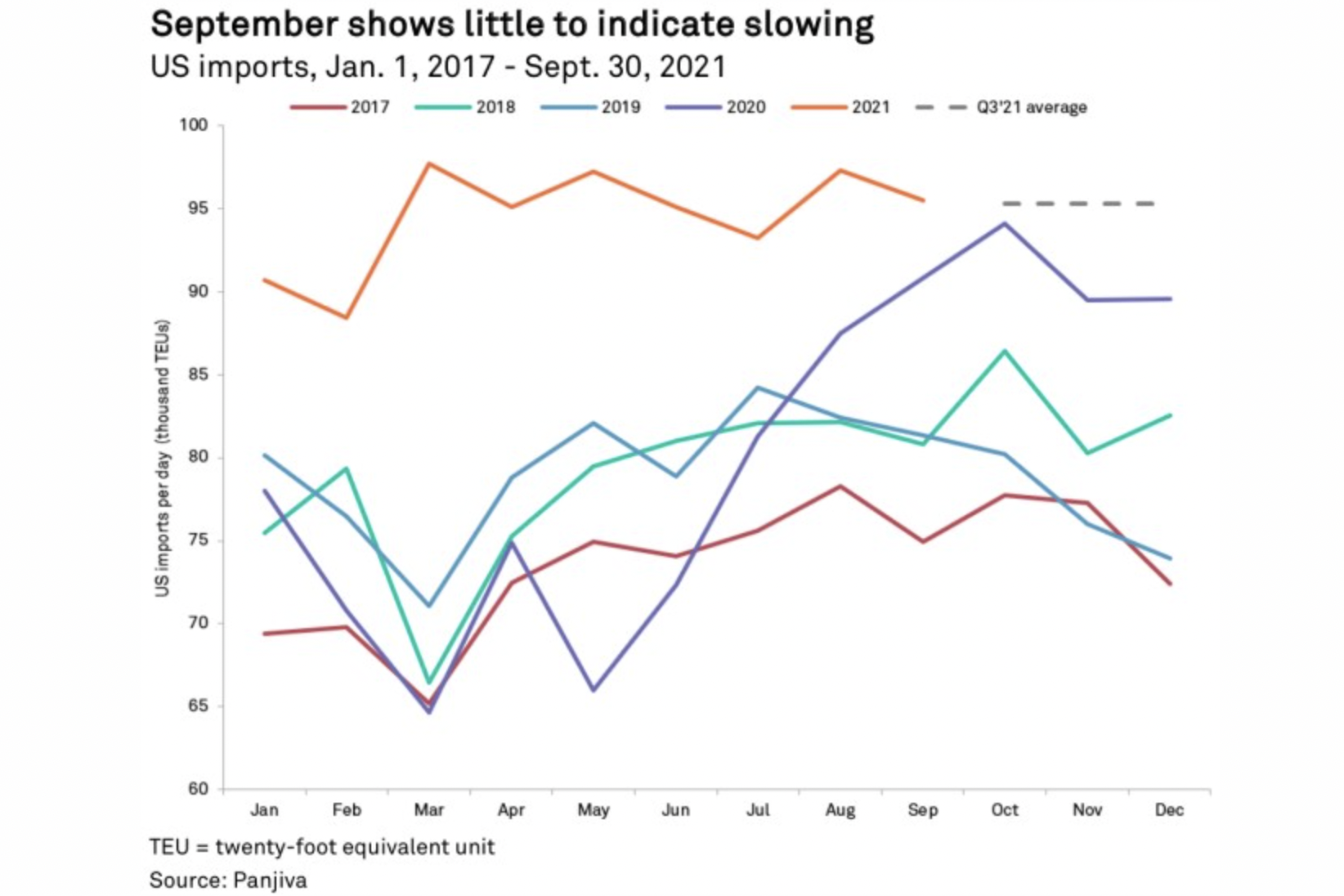

As a result of this buying binge, the United States is now actually importing more physical goods than ever before. That may sound a bit strange, given all the focus on how supply chains are in disarray. But it’s true. Measured by shipping container volume, imports were up 5 percent year-over-year in September, and up 17 percent compared with the same time in 2019, before the pandemic, according to the latest report from Panjiva, the trade data firm owned by S&P Global. (Panjiva’s numbers only include goods that have been processed by U.S. customs officials, meaning they only cover items that have actually been unloaded, not the freight waiting offshore.)

This unprecedented tsunami of stuff has swamped America’s ability to unload, warehouse, and transport it all. There are only so many berths where cargo ships can dock, and only so many cranes to unload them. There are only so many trucks that can enter and exit the port at a time, and only so many warehouses where goods can be stored. And there are also only so many trained dock workers or truck drivers available to actually do these jobs. So while enormous amounts of goods are arriving, individual shipments—whether it’s a new container of shirts destined for J.Crew, or an office chair you ordered on Amazon—have to wait in a long line to make it through to their final destination.

“More goods are getting into the country than ever before,” Eric Oak, a trade analyst at Panjiva, told me. “What we’re seeing though is that, at the more granular scale, at the company level, at the consumer level, that doesn’t mean that the good that you want specifically is going to be available.

”I like to use the analogy that it’s like two dogs trying to get into your house through the same dog door,” Oak added. “You’ve imported twice as many dogs into your house, but it’s probably going twice as slow.”

Part of the issue is that global supply chains are only designed to operate at peak capacity for a few months of year, usually in the lead-up to the holidays. Ports and warehouses can then work through any backlogs during slower seasons. “The problem is you’ve essentially had peak season since the onset of the pandemic,” Phil Levy, Flexport’s chief economist, told me. As a result, there hasn’t been a chance to play catchup after things get clogged, and so delays have simply stacked up.

Another subtle factor is that, while imports have surged in general, they haven’t increased evenly across categories. Panjiva’s data show that compared with last year, industrial goods and toys are way up. But consumer staples like soaps and cosmetics are down almost 20 percent. (Again, that may have something to do with any detergent shortages you’ve noticed.)

Experts I talked to were somewhat skeptical that the Biden administration could truly do much to pull the U.S. out of its supply chain mess. Aside from keeping the Port of Los Angeles open for more hours, the White House announced that it had gotten commitments from major logistics companies and retailers such as Walmart, FedEx, and UPS to move goods at all hours. The coordination effort might help. But in order to make a difference, companies will need to find more truck drivers—of which there’s a purported shortage—and more experienced port workers. That, or they’ll have to find people willing to pull a lot of late-night overtime. “I don’t think there’s a magic wand that’s going to make those resources appear,” Mary Lovely, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, told me. Industry leaders seem similarly pessimistic. “There’s no political intervention that’s going to get this done, and there may not be a human intervention that gets this done because this issue is now going to last well into next year,” Steve Pasierb, the president and chief executive of the Toy Association, said recently.

So Christmas shopping might be a bit frustrating this year, and visiting the store might not feel normal again until our spending patterns calm down. But it’s important to look at the bright side of the situation. America, after all, is still in the middle of a pandemic that led to millions of layoffs. But because our government has supported household incomes by sending checks and extending unemployment insurance, the country is also in the midst of a retail spree that has just happened to tangle the supply chain. As the Harvard economist and former Obama adviser Jason Furman has pointed out, it’s basically a luxury problem compared with the aftermath of the Great Recession, when families were simply broke. “The only reason we’re having supply chain problems is because people can afford to buy things and are buying things, which is much better than the alternative,” he told me. He added that versions of this story are playing out all over the world. “It’s more severe in the United States, but it is happening to various degrees everywhere. This is the first recession where in the U.S. and most other advanced economies, people’s incomes were protected. So there’s actually booming spending on durables and retail in all of the OECD countries.”

The irony of our supply chain woes is that shoppers can’t find what they want while they’re buying more stuff than ever. In that sense, we’re victims of our own success.

Correction, Oct. 15, 2021: This post originally misspelled Shenzhen.