Don’t Read His Lips

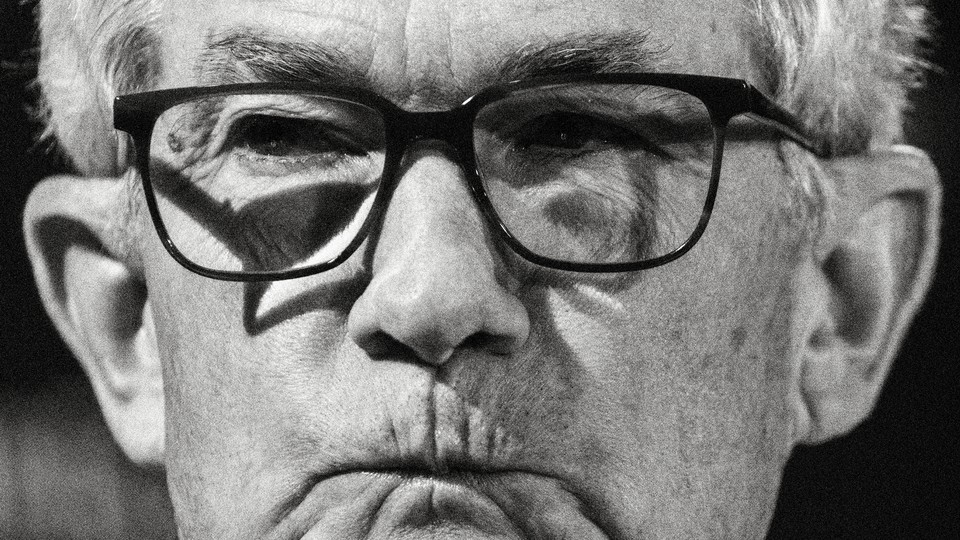

Jerome Powell has a tough job as chair of the Federal Reserve, trying to make Fed policy perfectly clear. Is anyone listening properly?

When Jerome Powell, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, spoke last week after the Fed’s monthly meeting, he was trying to convey the message that the fight against inflation was not yet won, and that the Fed anticipated continuing to raise interest rates over the next few months. “We’re talking about a couple more rate hikes,” he said, adding that the Fed needed “substantially more evidence” to be confident that inflation was falling.

All in all, it seemed like a straightforward presentation of the Fed’s outlook. But investors ignored it, because of something else Powell said: namely, that “the disinflationary process has started.” Once investors heard the magic word disinflationary, they leaped to the conclusion that the Fed was no longer as hawkish as it had been—and sent stocks soaring.

So when Powell spoke yesterday at the Economic Club in Washington, D.C., he wanted to make sure that no one missed the point. Although he did again use the word disinflation, he said the process of getting inflation down would be “bumpy,” and was likely to take “quite a bit of time,” and added that “more rate increases” were in the cards. Investors have been betting that the Fed’s tough talk is just a bluff, and that it will actually end up cutting rates before the end of the year. Yesterday, Powell seemed to be saying, Don’t test us.

This kind of public jawboning—or gentle nudging, depending on your perspective—to manage investor expectations has become so familiar from Fed chairs that it’s easy to forget how new a practice it is. For most of the Fed’s history, its members almost never commented on monetary-policy decisions when they happened, and rarely said anything about what they anticipated the future path of interest rates would be. (William Greider’s 1987 book about the Fed was appropriately titled Secrets of the Temple.) Until 1994, the Fed didn’t even announce at its monthly meeting whether it had raised or lowered interest rates: People figured it out after the fact by watching what happened to interest rates.

Since then, though, the Fed has moved steadily toward more transparency and more public communication about its thinking. Chair Alan Greenspan may have prided himself on his mastery of obfuscatory Fed-speak—he once said, “If I seem unduly clear to you, you must have misunderstood what I said”—but in 2003, during Greenspan’s tenure, the Fed for the first time made a statement about its expectations for future policy moves.

The big change in Fed communications came with Greenspan’s successor, Ben Bernanke. Bernanke was a firm believer in transparency and open discourse as virtues in and of themselves, but he also thought—correctly—that if the Fed was clearer about what it was trying to achieve with its policy, the markets would be more likely to respond to new financial data in a way that reinforced what the Fed wanted them to do.

In 2011, Bernanke held the first-ever scheduled news conference by a Fed chair; the following year, he laid out for the first time an explicit non-inflation policy benchmark, saying the Fed would keep interest rates near zero as long as unemployment was above 6.5 percent. Bernanke’s successors—Janet Yellen and Powell—have been similarly open. And other Fed governors now routinely weigh in publicly on the state of the economy and monetary policy.

What’s interesting about this shift is that it has changed the job of central bankers: Fed chairs don’t just have to be good at making policy. They now also have to be good at communicating. And they have to do that without any real rule book. You can see why Greenspan preferred to be gnomic rather than clear: That makes it easier to avoid inadvertently saying something that can, in Greenspan’s terms, be “misunderstood”—such as the word disinflation.

The solution should not be a return to the days of Fed-speak, though. Rather than emulating Greenspan, the better strategy for central bankers is to just explain clearly what they’re thinking and give up on the idea that the right combination of words will move markets in the perfect direction.

Yesterday, after all, Powell did a fine job of explaining that the Fed wasn’t convinced it had inflation under control, that it was sticking with its target of 2 percent inflation, and that, as a result, it planned to keep hiking interest rates. But it didn’t matter: After falling briefly in response to his comments, the market rallied strongly, and by day’s end it was up by more than a percentage point. Sometimes, the market just hears what it wants to hear.